I remember clearly the day my father was arrested. I was three years old and had already lived in an endless cycle of rented houses and high-end hotels, alternately enjoying the spoils of his work and the paranoid delusions of a life on the run. My father was an outlaw—one of the biggest marijuana smugglers working in the late 1970s, and a man few barely got to know. Though Dan McGuiness’s name has been omitted from most books on that time, a forgotten footnote in the DC-8s and shipping freights of the burgeoning pot business of 1977, for me his legacy became a powerful anchor, defining who I was.

In 1980, when President Ronald Regan came into office, one of his first acts was to target the smuggling trade that had run rampant along the Eastern Seaboard under Carter’s charge. The culprits were young men like my father who had made fortunes smuggling through Panama and the islands off the coast, hitting ports of entry like Miami and New Jersey, and behaving like the Pirates of the Caribbean that had sailed centuries before. They gave themselves nicknames like Chief and Silent Dan and Big Jim, and lived in big houses in Florida and Jamaica—snorting coke, smoking weed, and swilling whiskey and women. They were removed enough from Cartel life to feel safe, yet close enough to prosper.

My father prospered. We were always on the move. We’d go from Boston to Florida, Jamaica to East Hampton, Maine to Connecticut, as my dark Irish father partied, playing pool in in the basement with his cronies, and my mother ironed sheets upstairs in the bedroom. She was terrified of this life she had stumbled into by marrying the dashing man she met while on vacation in Ft. Lauderdale. A year after they married, they had their first and only child—me.

And then he was arrested. When my father was sentenced, the U.S. District Attorney decided to make an example out of him. Tired of those Jimmy Buffet outlaws, flying high and thumbing their noses at the federal justice system, the courts saw my dad as the perfect poster boy. He wasn’t a tall man, but with his thick black curls, tan, muscular forearms, and quick, slight gait, he had all the hubris of the largest guy in the room. The judge sentenced him to 66 years with no parole.

In one day, we lost everything, and I can’t help but think that, despite the uncertainty of her future, my mother felt relief as much as fear. Though the houses and cars and high-end luggage were gone, we had peace. We moved to Dallas. We lived in middle class neighborhoods as my mother and grandmother worked to give me a normal life while my father sat behind bars in a long list of federal prisons.

I went on to private schools and good friends. My innocent dimples, blonde hair and blue eyes may have made me appear as naïve and sweet as my mom, but I desperately longed to be my father. The plaid school uniform, the cheerleading skirt, the Gap clothes from where I worked just didn’t fit the other side of who I was. My friends were all upper-middle class, and they didn’t have my story. Sure, they had alcoholic fathers, molesting uncles, and mothers who didn’t offer them the support and understanding they needed as growing women. But my dad was in prison.

In other neighborhoods, I would have been one amongst many. But in mine, I felt lost—caught between the full-moon fever of my early childhood and the tempered suburban-ness of my school years. As I grew up, I saw my father’s world glorified in movies and TV—Scarface, Godfather, and even Miami Vice. All I knew was that if my Daddy would come home, we would be restored to the grandeur of the party, and saved from the monotony of playing it straight.

At my first all-night party when I was 18, I sat on a roof with friends from college, sipping martinis until six in the morning, and I thought, “Finally. This is more like it.” I knew that this was all my dad had wanted. The life with no rules—where society is rejected and rebellion realized. My way became the high way, and I became closer to my dad in the process. Throughout college, he would call me from his federal prison in Lompoc, California, and I would tell him about the different types of weed we were smoking, and which whiskey I liked best. He would warn me about the dangers of coke, but then laugh and say, “Hell, you’re young. Enjoy it.”

And for years, I did enjoy it. I lived in the self-absorbed haze of drinking and drugs. I languished there, thinking of all the brilliant and wonderful things I was going to do once I woke up. But I could never get to sleep. Flaunting my father’s previous occupation and ongoing incarceration, I wore his life like it was a badge of cool. I searched for him in those long nights, echoing his behavior as a way to bring him back, resurrecting a ghost lost behind bars. Losing myself around pool tables, taking down eight balls, I failed to show up for anyone—including myself.

By the end of my drinking, I was tired of losing. I was tired of the swollen eyes, the dilated pupils, the strange cases of bronchitis and pneumonia, and the constant threat of things like eviction, repossession, debt, resentment, and heartbreak.

And my father’s life didn’t look so attractive anymore. He was released in 2004 for the first time, and spent the next five years in and out of prison because he couldn’t stop smuggling. He didn’t know or want to do anything else, and he risked our relationship at every turn. Not understanding why I would want him to be present, he would get angry when I asked him to be different—to be my dad. After I got tired of having to constantly worry as he made dangerous runs between Nogales and Phoenix in the midst of the 2008 border wars, I began to stop caring at all. The alcoholism that I had recovered from was present in his life, fuelling his primary addiction to crime, numbing him from the real and present danger in which he lived. My father loved the big deal, the prospective score. He wanted the adrenaline rush of knowing that he won, that he got away with it, that he beat a system that could really care less about him, and that he lost everything to do it.

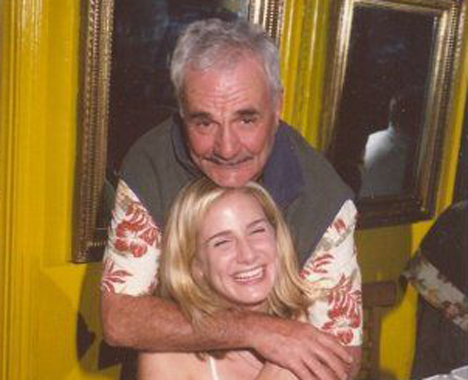

When my father passed away in 2009, relief swept over me like it had my mother 25 years before. After decades of dragging the stone weight of his choices, I was exhausted by the whole mess. I loved him, I will always love him, but I also knew there was nothing I could do, no change I could invoke. People are who they are until they hurt enough to change and, after 25 years in prison, my father had lived in hurt for so long, he disconnected from it. Unable to stay in the pain, he ran instead.

At my father’s memorial, people told beautiful stories about him—funny, endearing, sad visions of a man who was only caught in glimpses. He never stayed in place long enough for anyone to really get to know him. As for me, I finally stopped looking for him in the restless addictions we once shared. Three months after he passed, I released his ashes in the ocean. Standing on the back of a speedboat driven by my uncle, we took off against the waves of the Pacific. My father’s ashes spread out behind us. The pirate was back at sea.

Kristen McGuiness is a freelance writer and regular contributor to The Fix who wrote previously about the 13th step and dreaming about drinking. She is the author of 51/50: The Magical Adventures of a Single Life.