As questions erupt over officially sanctioned snooping into Americans’ online activities, at least one thing is clear: The feds are watching what you do on the Web. Still, the promise of online anonymity continues to tantalize, and increasingly sophisticated anonymizing and online-commerce services have created a burgeoning segment of the black market—and that, naturally, means drugs. Can the Internet take over drug sales the way it already has for books, music, shoes and everything else—or is it just another place to get caught in a surveillance state?

Terrorism remains the official main target of spying by the National Security Agency, but black-market commerce has started attracting federal interest, too. In late May, the US Department of Justice (DoJ) announced its largest successful online money-laundering sting against the Costa Rican-based Liberty Reserve, whose anonymous operations “became a popular hub for fraudsters, hackers and traffickers…including underground drug-dealing Websites,” the DoJ indictment read.

Liberty Reserve helped launder $6 billion and processed 55 million transactions that were “overwhelmingly criminal in nature,” according to the DoJ. In closing down the site, the DoJ seized Liberty Reserve’s domain name, about $25 million in assets and 45 related bank accounts. The DoJ also made five arrests, including that of Arthur Budovsky, Liberty Reserve’s founder.

While $6 billion is no small chunk of laundered change, it pales in comparison to what cash cartels have funneled into legitimate banks. Liberty Reserve moved that amount over the entire course of its seven-year existence, but British banking giant HSBC permitted $7 billion in unmonitored transactions in Mexico, consisting largely of drug money, over a single year (2007-2008), according to a Senate report. (The DOJ hasn’t fingered any of the specific drug-dealing sites that used Liberty Reserve.)

Trade volumes aside, Liberty Reserve and hundreds of other anonymous Internet payment systems highlight the challenges online currencies pose to law enforcement and the attractions they offer to criminals. It’s not primarily that the currencies make payment easy for consumers, as with PayPal and other legitimate e-commerce—it’s the anonymity.

This anonymity “makes it much harder to find who the sellers are,” Nicolas Christin, associate director of the Carnegie Mellon Information Networking Institute, wrote in an email to The Fix. “Even the buyers are hard to trace.”

Liberty Reserve, described by Internet security blogger Brian Krebs as “insanely secure and redundant,” protected users’ anonymity through a variety of measures, DoJ officials stated. First, by setting up Liberty Reserve in Costa Rica, Budovsky hoped to avoid US agents. And the company, unlike traditional banks, required no identifying information from users. Liberty Reserve clients could easily register blatantly, even comically criminal-sounding pseudonyms. One undercover DoJ agent signed up for Liberty Reserve as “Joe Bogus,” filing his accounts under “for the cocaine.” Try that at Chase.

Silk Road’s URL is designed never to leave a trace in Google or other browser searches, and clicking on it won’t take you anywhere.

Anonymity and the Internet, of course, have long gone hand in hand. From the early chat rooms to today’s comment sections, the Web lets you hide behind any avatar you like. The (perceived) low risk of identification, combined with the high profits of the drug trade, made it inevitable that drug sales would migrate online, Eric Sterling, Criminal Justice Policy Foundation president and a lawyer who helps draft drug policies, told The Fix.

Old-school Web attempts to sell drugs online, however, show just how shallow the base levels of Internet anonymity are. Peddling drugs on Craigslist, for instance, is as common as it is risky. The 21 New Yorkers recently cuffed for vending prescription painkillers (among other drugs) on Craigslist can attest to the slim identity protections their ads granted them. The vast majority of such sales are digital versions of street-corner drug dealing. Law enforcement is increasingly cracking down on Craigslisters as traffic in addictive opiates like Oxycontin and stimulants like Ritalin begin to rival the cocaine and heroin trade.

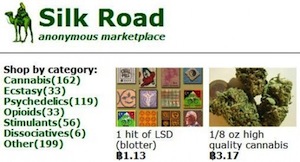

But compared to Craigslist, and even to Liberty Reserve, state-of-the-art online anonymity is harder to crack because it takes different tacks, Christin said. That’s particularly true of Silk Road, the Internet’s biggest digital drug bazaar. The site, which went live in 2011, exploits several technological advances. First, its transactions use Bitcoin—dubbed “crypto-currency” —eliminating the identifying information associated with credit cards and other e-commerce methods. Second, the site occupies a darkened section of the Internet, tucked beneath the overpasses of the information superhighway. In this shadowy ‘Net, URLs are designed to never leave a trace in Google or other browser searches: You can find Silk Road’s address easily enough, but clicking on it won’t take you there—or anywhere.

Because Silk Road is not reliant on Liberty Reserve funds, it escaped the current prosecution. But the site gives an idea of the volume of drug business taking place on such exchanges. “A relatively significant market,” Silk Road collects about $1.2 million in revenue every month, according to a 2012 study by Carnegie Mellon’s Christin. The site’s user forums estimate 30,000 to 150,000 customers, and Christin counted a few hundred dealers.

Silk Road’s popularity highlights the loyalty of its satisfied customers, who appreciate its self-regulating system. Shoppers rate the reliability of sellers and the quality of their products just as on eBay. You can also communicate by email with the seller. If you decide on a purchase—a gram of Afghani hash, say, or 10 hits of LSD on blotter paper with the big blue Avatar faces from the James Cameron film—you add it to your shopping cart and press “check out,” typing in your address and paying with Bitcoins. In about a week, you’ll get a vacuum-sealed, disguised package, dropped off by your postman.

The obscurity of Silk Road is possible thanks to Tor, or The Onion Router. This network allows users to interact anonymously, hiding their location, usage and other ID by ricocheting all information through a series of randomly selected encryption relays. “There isn’t any such thing as perfect security,” Christin said, “but accurately pinpointing Tor hidden services is not easy.”

Because of its fortress-like defenses against surveillance, Tor’s free software is a favorite of privacy advocates and outlaw traffickers alike. (And of Edward Snowden, the leaker who first exposed the National Security Agency’s dragnet of Americans’ digital data. He reportedly keeps a Tor sticker on his laptop.)

The very newness of these sites and services has also appealed to criminals, Steven Wisostsky, a professor at Shepard Broad Law Center who studies drug law enforcement, told The Fix. Bitcoin was launched in 2009; Tor developed from a US Navy project begun in 2002, spreading to non-military uses over the years.

“Because Bitcoin is out of the mainstream, it has fallen under the radar,” Wisostsky said. “But it looks like prosecutors are looking into it now.”

Indeed, the Liberty Reserve case signals a significant strategy shift, Christin said. “Certainly law enforcement is now taking these online currencies very seriously and is trying to regulate them.” In March, the US Treasury Department announced that money-laundering rules would apply to online currencies like Bitcoin. Officials say to expect more regulations going forward.

Bitcoin poses a tougher target for law enforcement than Liberty Reserve, however. For one thing, Liberty Reserve’s use was primarily criminal. But more important, it was centralized—the base company, headed by Budovsky, could be decapitated, and the currency’s website seized due to direct involvement in criminal money laundering.

By contrast, Bitcoin relies on money transfers from user to user instead of a central site. “Liberty Reserve was rather easy to find,” Christin said. “Everybody knew who was running it, and stopping them wasn’t technically hard once the indictment was built. For Silk Road, it is going to be a lot harder.”

But Bitcoin’s decentralization comes with costs as well as benefits. Freely floating currencies like Bitcoin fluctuate wildly in value—for example, its exchange rate dropped over $100 during a particularly volatile day in April. These digital monies can therefore serve reasonably well for the small purchases that dominate Silk Road, which is “essentially replacing the street corner ‘weed guy,'” Christin said. But for some of the bigger criminal enterprises that relied on Liberty Reserve’s accounts, the instability of Bitcoin just won’t do, Krebs wrote. The blogger quoted a commenter in a crime message board who imagined paying someone $1,000 for “a job,” with currency fluctuations shrinking that to about $600 before withdrawal.

Even so, its association with sites like Silk Road could make things hot for Bitcoin, Christin said. Law enforcement has a number of options for targeting Silk Road, as some officials want to do, including targeting Bitcoin or Tor. Officials could also tighten controls around the postal systems used for delivery.

And Bitcoin’s users should not expert it to be impervious to law enforcement, warns Jeff Garzik, a member of the currency’s development team. All Bitcoin transactions of the anonymous online currency are recorded in a public log, making users vulnerable to decryption. “Attempting major illicit transactions with Bitcoin [on Silk Road], given existing statistical analysis techniques deployed in the field by law enforcement, is pretty damned dumb,” Garik told Gizmodo.

The first Silk Road criminal conviction occurred last January when an Australian man bought suspiciously large quantities of MDMA, amphetamines, marijuana and cocaine from a Dutch source on the site with the intention of setting himself up as a Silk Road supplier.

“Attempting major illicit transactions with Bitcoin on Silk Road, given techniques deployed by law enforcement, is pretty damned dumb.”

While such “dumb” Bitcoin users may end up next to Craigslist dealers in cuffs, don’t expect to see a wholesale shutdown of Bitcoin or Tor, as happened with Liberty Reserve, Christin said. Budovsky’s service survived primarily on a diet of criminal transactions, whereas Bitcoin looks set to function as a widely useful, aboveground commerce system (its current economy is estimated at almost $40 million). So stifling Bitcoin would disrupt many legitimate businesses. Other options are available, including targeting the exchanges that handle Bitcoin transactions, as in May, when authorities froze MtGox, Bitcoin’s largest exchange.

Tor, meanwhile, arguably serves more vital functions, helping dissidents secure anonymity and evade censorship in repressive regimes (one of its major sponsors is the US State Department). “Disrupting the entire Tor network for the purpose of taking down Silk Road would come at a high collateral cost,” Christin wrote in his Silk Road study. The network has also proven difficult to take down due to its open design.

Moreover, the whole whack-a-mole game of the War on Drugs will continue no matter what the authorities do to Tor, Bitcoin or any other site. “You could get rid of all these virtual currencies, and they’d find somewhere else to put it,” Thomas Nicholson, a researcher in drug policy at Western Kentucky University, told The Fix. Online black markets are just the latest iteration of the moneymaking criminal realms birthed by Prohibition, which remains the official US position regarding recreational substances, Nicholson said.

In any event, online narcotics trafficking is only a tiny segment of the global drug enterprise. When the Liberty Reserve bust was publicized, many observers noted the War on Drugs’ double standard. The DoJ’s criminal prosecution of Liberty Reserve, which laundered money for relatively low-level cyber-traffickers, contrasts almost comically with the $1.9 billion wrist-slap settlement granted to HSBC (equal to five weeks’ of company profits), critics said. This mild punishment came down on a bank caught colluding with global drug cartel kingpins (a violation of the Trading With the Enemy Act).

Unless the legalization trend begun in Colorado and Washington spreads nationwide, the narcotics trade will remain enormously profitable—both for crypto-banks and for too-big-to-fail real-life banks—and the Internet will likely find intriguing new ways to shuffle the drug money.

Michael Dhar is a medical and science writer who has written for Livescience.com, Science & Medicine, Iowa Outdoors and various medical and research institutions.