Inmates released from the Queensboro Correctional Facility in New York City are being sent off with naloxone kits, and the training to use them in their own communities back home.

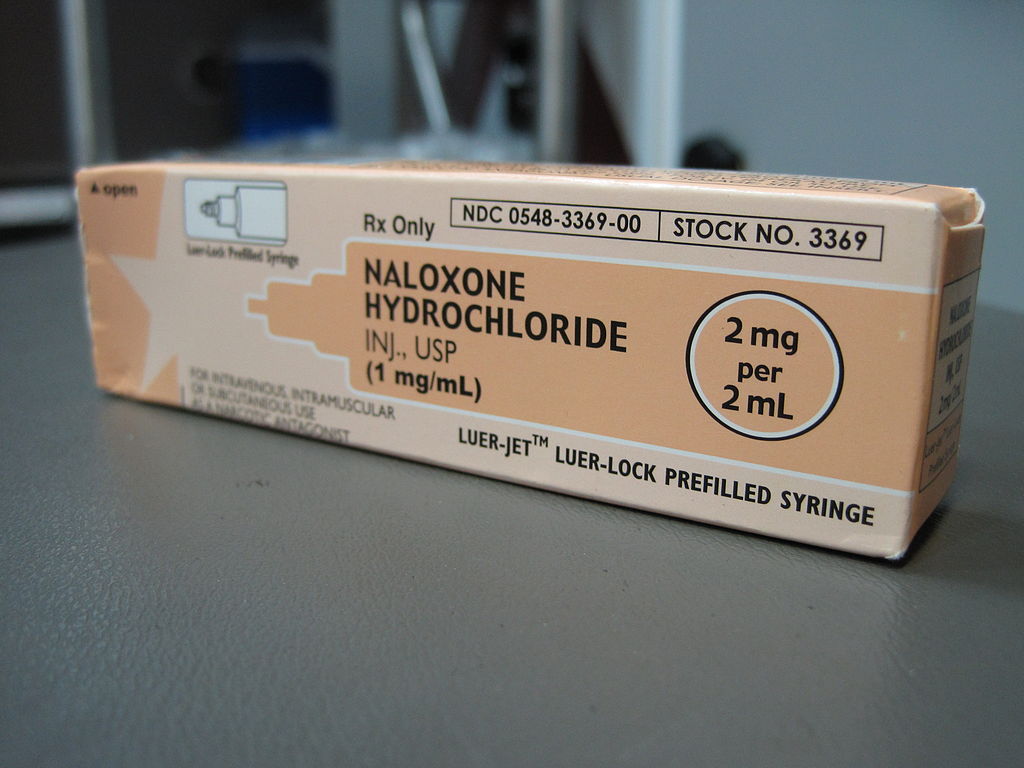

The pilot Opioid Overdose Prevention program launched in New York in February 2015, starting at Queensboro. Inmates are taught how to use naloxone—the antidote which reverses the effects of opioid drugs—and are educated on the state’s Good Samaritan Law, which protects those who seek help in an overdose situation from prosecution. Once they complete training, they receive a naloxone kit to take with them when they are released from prison.

Since the start of the program last year, a handful of discharged inmates have reportedly used the naloxone kits and saved lives. WNYC radio station spoke to one of them, Kevin Small, who had recently been discharged from the Edgecombe Residential Treatment Facility in Manhattan when he spotted a man he recognized, passed out on the sidewalk. Small said he knew the man had a history of heroin use so he took action, called 911, reached into his kit, administered a series of doses, and watched the man regain consciousness.

The program has expanded to other New York State prisons over the last year, according to WNYC. It is expected to be introduced to all 54 correctional facilities statewide.

This is a meaningful step toward educating and equipping a population that is especially vulnerable to the consequences of opioid abuse. Opioid users who transition out of prison are at particularly high risk for an overdose, according to a 2015 report in the Harm Reduction Journal. And studies have shown that newly released prisoners have very high rates of drug overdose deaths.

WNYC spoke to Dr. Sharon Stancliff, medical director of the Harm Reduction Coalition, who put the program in perspective. “The first weeks and months after somebody is released from jails or prisons they have an extremely high chance of dying of overdoses,” she said. “They’re going back to communities where drug use is widespread, so it’s both about making sure that they stay alive in those really vulnerable times, but also giving them tools to save lives in their own community, and I think that’s a very positive message for people who are leaving prison.”