I never thought much about meditation until I got sober. Then, suddenly, all sorts of words I’d never considered—meditation and prayer among them—started popping up in conversations. Though I was raised as an unobservant Jew, I was open to the prayer discussion. But whenever people started talking about the various forms of meditation they did, I’d usually offer up the fact that I was one of those people who simply “couldn’t” meditate. I’d usually add that I couldn’t be hypnotized, either. Then I’d tend to feel a bit guilty and change the subject. When I got to the 11th step, did I let a pesky instruction about how I should be seeking “through prayer and meditation” to improve my “conscious contact with God” get in the way of that? Not really. I kept at the prayer I’d learned from my first day in program, figuring that doing half of the 11th step was better than not doing it at all.

Then, when I was about three years sober, a girl I knew from program dragged me to a lecture by a meditation teacher named Thom Knoles. I only went because I wanted to be friends with this girl and, when I saw all the people gathered at the West Hollywood apartment for what was being billed as a “knowledge meeting,” I wanted to be friends with them, too. I recognized many from 12-step rooms throughout LA; they were all attractive and, if not incredibly happy, then at least very much appeared to be.

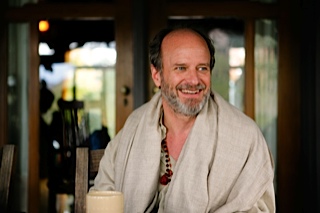

Knoles began talking. I don’t remember the first thing he said but I know the first thing I heard: that the type of mantra-based meditation he taught—Vedic Meditation—stopped the aging process. As I began to listen to a lecture that I’d planned on tuning out, I was shocked to discover that everything he mentioned intrigued me just as much as the notion of being able to stay looking young without surgical measures. He discussed the way that stress builds up in the body—how we’re born with a fight or flight impulse that our ancestors needed because it provided them with the strength required to, say, fight off a wild boar but which, in modern-day society, simply fills the body with stress (the example he gave us was when we slam on the brakes of a car and suddenly have enough adrenaline to fight off that boar of yesteryear). The stress, he told us, just keeps on accumulating—until we learn to meditate and can break it down. He talked about how people worry too much about staying focused while meditating but that it’s okay if your mind wanders because that’s just stress that needs to be released from your body. He said that Vedic Meditation is five times more restful than sleep. He talked about it all in an incredibly amusing and knowledgeable way. He was, quite frankly, the most articulate person I’d ever heard speak.

I meditate, I’ve come to realize, because sitting and repeating a mantra in my head helps me when I’m not meditating to, as the Big Book suggests, “pause when agitated.”

At the end of the lecture, those who were interested in learning Vedic Meditation from him that week made a donation (the suggestion was a week’s salary) and agreed to show up three times over the next few days for hour-long combination lecture/meditation sessions.

Not entirely sure what was guiding me, I made my donation and then, even more surprisingly, showed up the next day, bearing flowers and fruit as I’d been instructed, to get my mantra from Knoles. Far more shocking than all that is the fact that, for the past seven or so years since, I’ve continued to practice what I learned that week—meditating for roughly 20 minutes every morning and 20 minutes every afternoon (though I have, of course, missed days).

I must confess that I’ve never, in all the time since, had someone rush up to me and ask me how on earth I manage to emanate such a relaxed vibe—nor do I feel like I’m remotely at risk for that happening. I don’t often experience the transcendental part of meditation (a state Knoles describes as “where there’s no mantra and no thought…just for a millisecond or second at a time”). But meditation has been, from the first moment I learned it, an intrinsic part of my sobriety—and of my life. And basic facts—say, for instance, the fact that I’d wanted to write a book my whole life but never had the patience for it until I started meditating—are impossible to ignore.

But I didn’t learn how to meditate so that I could write and sell books. I did it, I’ve come to realize, because sitting and repeating a mantra in my head helps me when I’m not meditating to, as the Big Book suggests, “pause when agitated.” I do it because I once had so much trouble being in the moment that I’d ingest drugs that had started to make me feel horrible in order to get out of it. I do it because I need as much help as I can get living a life that allows for no checking out. But mostly I do it because I like it.

Although Knoles is only in Los Angeles in spurts—he lives in Flagstaff, Arizona, where, he estimates, he spends roughly 45 percent of his time—I’ve managed to keep up with him over the years. And my original impression of him—that he was the most articulate person I’d ever heard speak—has remained consistent. And this is one of the many reasons why I wanted to find out more about this man that’s had a greater impact on my sobriety than many of my sponsors and is as close a thing to a guru as I’ve ever had.

Now 64, Knoles is the grandson of an Arizona senator and the son of a Pentagon general and TWA hostess. He came to meditation by way of yoga, which he learned when he was 15 and his family was living in Washington DC. “One day [in 1968], one of the people at the yoga school said, ‘There’s an Indian master coming to town and he’s going to give a talk,’” Knoles recalls now. He went to the talk, and, along with hundreds of other people, received a mantra from this Indian master—otherwise known as Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the man who’s famous not just for developing transcendental meditation and teaching it to the Beatles but also for laughing so much in his television interviews that he became known as the “giggling guru.”

Years later, when Knoles was still a teenager, he had a follow-up meeting with the Maharishi—and was singled out from the crowd. “He said to me, ‘What are you doing these days?’” Knoles remembers. When he explained that he was thinking of studying psychology, the Maharishi simply responded, “Come with me and I’ll complete your training.”

Knoles spent the next two decades traveling around the world with the Maharishi and an entourage of others, soaking in as much as he could. He would periodically break off on his own, and by the age of 20, already had a substantial following as a meditation teacher. (Knoles isn’t associated with the Maharishi Foundation Limited, a US-based corporation that has trademarked the words Transcendental Meditation.) After receiving a doctorate in neuroscience in 1978 from the Maharishi European Research Center, Knoles launched his career as a public speaker and educator; later he studied alongside Deepak Chopra to become an Ayurveda educator. While these days, Knoles visits cities like LA, San Francisco and New York training other teachers who then build their own client bases (46 so far), he estimates that he alone has taught nearly 21,000 people throughout the United States, Australia, Europe and India (he speaks Hindi).

It’s easy to see how Knoles has been able to attract so many high-profile followers (including producer Ryan Kavanaugh and Lions Gate COO Joe Drake) and to spread meditation so far and wide: he has the unique ability to make you feel not only seen and understood but also somehow special. No matter what questions he’s being asked to answer during his talks—and trust me, I’ve heard some doozies—he manages to both have an interesting answer and also to make the question somehow seem if not necessary, then at least significant.

I still remember how confused I was when Knoles first gave me my mantra—a three-syllable sound that didn’t mean anything to me when I heard it but which I found almost inexplicably soothing from the moment I began repeating it to myself. But his manner was incredibly calming as he explained the method. Apparently, we are each one of 10 classic body types and all have a “need” for a certain mantra based on that type; your mantra is thus “a charming sound that pulls you inward and away from all the surface layer thoughts” for your particular body type. (Because mantras are based not just on what Knoles calls “psychophysiological types” but also on life stages, there are thousands of mantras out there.)

“Addicts are the seekers of the world,” he says, adding, “People don’t become addicts because they want to have a bad experience—they’re people who are willing to try something to change their state of consciousness.”

It’s crucial not to repeat your mantra to anyone—something I’ve, rather shockingly, been able to follow—both because if people gave their mantras out willy nilly, those who heard them might try using them for their own meditation and conclude that they’re useless because they weren’t right for their body type. Also, Knoles says, repeating your mantra for someone is giving that person a chance to “trivialize the key that will give you access to your deep inner creative intelligence field.”

When I tell him that every knowledge meeting and group meditation session of his I’ve attended over the years has been filled with people I know from 12-step rooms throughout town, he admits that in LA in particular, he seems to have “hit the motherlode” of people in recovery. His rough estimate is that of the 10,000 or so Angelenos he’s taught, 75% of them are recovering addicts in program.

The fact that he’s drawn in the former party boys and girls doesn’t actually surprise Knoles. “Addicts, in my opinion, are the seekers of the world,” he says, adding, “People don’t become addicts because they want to have a bad experience—they’re people who are willing to try something to change their state of consciousness.” By this logic, those in recovery are therefore not only going to be drawn to the notion of escaping their thoughts but also, “when they learn to meditate,” Knoles says, “their brain starts producing regularly the kind of chemistry their body was craving, and the chemicals in the brain are far more satisfying than the chemicals in all those substances.”

I give Knoles a surely skeptical look and tell him that even though I get more out of my meditation than I can even articulate, I wouldn’t necessarily call what I experience in my brain as being as “satisfying” as some of my better drug experiences. “It’s not as immediate and not as strong,” he admits with a smile, “but true addicts have already figured out that immediate and strong is often like seeing the Grand Canyon by jumping over the edge.” He lets out one of his frequent laughs and adds, “They figure out that there’s got to be a hiking trail.”

But Knoles stresses that meditation will not, on its own, cure addiction. “One of the first things I do with somebody who is an addict and hopes that meditation is going to solve their problem,” Knoles says, “is tell them that I can introduce them to someone who might like to take them to a meeting.” Knoles, who’s never had a drink, taken a drug or smoked a cigarette, says that he’s “probably one drink away from being an alcoholic” since his dad was one. “It’s possible that I might one day take these things up,” he says. Then he laughs and it’s easy to trace his lineage back to the giggling guru. “I hope that if I do,” he adds with one of his beatific smiles, “somebody will get me in the program.”

Anna David is the Executive Editor of The Fix and the author of the books Party Girl, Bought, Reality Matters and Falling For Me. She’s written about sex addiction, gambling addiction, Thomas Jane, Tom Sizemore, and many other topics for The Fix.