Last Tuesday, in the dead of night, the New York Police Department staged a surprise evacuation of Occupy Wall Street’s encampment in Zuccotti Park. Hundreds of policemen decked out in riot gear descended on the protestors using deafening LARD (long-range acoustic devices) noise cannons—the same high-tech “non-lethal weapons” used by the US military in Iraqi. They also deployed pepper spray, tear gas, and flash-bang grenades to subdue the encampment. A street-by-street lockdown of the financial district was enforced, followed by a media blackout, blocking reporters from covering the forced eviction of the OWS protesters. Of more than 250 people arrested Tuesday morning were seven reporters and photographers, including those from The New York Times, NBC, the AP, New York Daily News, Fox News and New York 1. In a press conference later in the day, Mayor Michael Bloomberg said that the media were excluded from the scene “to prevent a situation from getting worse and to protect members of the press.”

Journalists were quick to condemn the lockdown and blackout of a major news event. Blogging for The New Yorker, journalist Philip Gourevitch wrote, “In a democracy, a mayor who believes he can shut down the press at will is not defending public safety; and a mayor who believes the police can be unleashed to manhandle the citizenry without answering for it cannot claim to be on the side of law or order.”

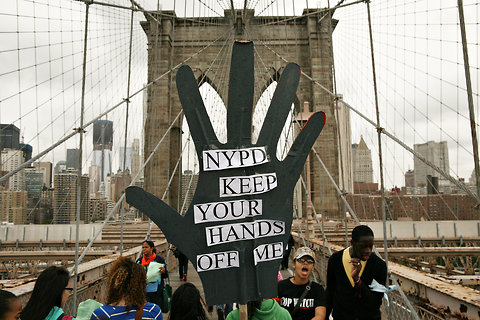

In fact, broad swaths of urban America live under similar “crackdown” conditions every day due to constitutionally slippery drug-war policies like stop-and-frisk, the controversial police practice of detaining, questioning and searching any person who is under “reasonable suspicion” of involvement in a crime. “Reasonable suspicion” is, of course, all in the mind of the cops on the beat, with all their prejudices and pressures. Once stopped, the person can be patted down if the police “suspects” they may be carrying a weapon; once frisked, the person can be arrested if the police find drugs or other illegal contraband in lieu of a weapon. In practice, stop-and-frisk allows the police to invade a person’s privacy in pursuit of any pretext to arrest them. Urban neighborhoods where drug trafficking is commonplace have some of the nation’s highest rates of stop-and-frisk, since even to set foot on (let alone live on) a block where a drug dealer operates is to come under “reasonable suspicion” of criminal activity, according to the police.

Journalists and researchers who work in these neighborhoods can be subjected to the same arbitrary restrictions as reporters trying to cover major confrontations between police and protesters. Like the press during the media blackout of the OWS eviction, they can even suffer the same violence at the hands of law enforcement.

Still, few people other than active heroin addicts would find themselves touring Camden, New Jersey, the notorious town across the Delaware River from Philadelphia known, in 2009, as the country’s murder capital. Even fewer would spend a Sunday morning checking out the network of heroin corners on the city’s north side. At least, that’s the assumption the Camden Police Department operates from when stopping drivers and pedestrians in the neighborhood, questioning, often frisking and continuously threatening them with arrest. It’s hard to argue with the department’s reasoning, which is probably at least more often than not true.

Camden was forced to lay off half of its police force this year due to budget shortfalls, unleashing what is reportedly a state of sustained chaos. On the surface it certainly looks like a place to avoid. North Camden consists of a tight grid of tiny row houses, many in a state of total collapse. Whole clusters of buildings that burned down long ago and were never demolished or repaired now barely remain standing as charred shells. Of those homes that haven’t burned, scores are boarded over with plywood stenciled “Department of Public Works” in black paint on their front doors. Interspersed among the ruins are vacant lots littered with garbage, broken glass, dirty needles, used condoms—the standard detritus of high drug-and-crime neighborhoods where the public sector has more or less stopped performing basic functions other than nailing boards over broken shooting-gallery windows.

Law enforcement’s assumptions about who should and who should not be in certain public spaces form the framework for Camden’s (and many other cities’) stop-and-frisk front-line drug -war policies. These policing practices have long been widely criticized as racial profiling; in a study of stop-and -frisk in New York City in 2009, African Americans and Latinos were nine times likelier to be targeted than whites, but, once stopped, no more likelier to be arrested. As for the use of force by the police, people of color were again disproportionately targeted, with cops drawing a weapon or throwing to the ground 27% of Latinos and 25% of blacks compared to 19% of whites. Although civil liberties advocates like the ACLU have challenged the constitutionality of stop-and-frisk laws in court, the Supreme Court has yet to reconsider its decades-old ruling that “reasonable suspicion”—and not only the stricter “probably cause”—could form the basis for stopping, searching and arresting someone.

When murders, especially shootings in the street, spiral out of control, as they did in Camden in recent years, public officials take a “by any means necessary” stance: the police can stop anyone—and possibly detain and search them—simply for being near a drug hot spot. Since nobody in their right mind who isn’t in the drug game would go to these neighborhoods in the first place, the logic goes, anyone found there is, by definition, under “reasonable suspicion.” Of course, this reasoning is false. These neighborhoods are home to many people too poor to escape them; they attend the storefront Christian churches every Sunday and view heroin, crack and other drugs as demonic scourges that have devastated several generations of their people. Yet advocates, researchers and social workers regularly engaged with these communities know that the street-level cops will do as they please, regardless of the effectiveness of their policing practices or the effects on the residents’ quality of life.

On a recent Sunday morning I was in North Camden doing research for a writing project, mapping out dope corners, making notes about gang graffiti and street memorials erected at recent murder sites. When doing field work I tend to take notes via Twitter, pulling over in my car to post observations and photos as I go.

Arriving at 8:30, I sent the following tweets:

“Dope corners up & humming at 8:30 am, patrol car perma-parked on the corner of 6th and York.” An officer was posted in his vehicle in an abandoned lot that sits on one of the city’s hottest drug corners and was flipping through the Sunday paper, looking like he wasn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

Then, a few minutes later: “3 more dudes try to flag me down like I’m looking for dope between 5th and 8th on Vine.” Hustlers and police alike make the same false assumption that that guy cruising these streets in his car (me) is a likely drug customer. The fact that I may be North Camden’s only devoted sightseer would never cross their mind, nor would I expect it to.

The next tweet I posted took even me by surprise: “Oh man, almost just got locked up by Camden’s finest, dude totally pinned me with his squad car & threatened to take me in.”

That I was stopped and almost arrested for being in a high drug-and-crime area may seem somewhat like an anticlimax. How else are the cops and the dealers supposed to explain the presence of a white guy in his thirties casing the neighborhood? Yet it was surprising to me because in many years of being deeply involved professionally in these neighborhoods, I had never before been detained and interrogated by the police (tailed a couple times, but not stopped). I wasn’t doing anything illegal, but my very presence there was sufficient to place me under “reasonable suspicion.”

I was driving along 10th Street when the sight of one of the neighborhood’s Latino corner-hustler kids hauling ass across a vacant lot like he was being pursued caught my eye. I watched the direction he was running and made a left turn onto Cedar hoping to not intersect with him. (I had once been pinned down in my car by drug-corner gunfire during a similar chase scenario while doing social work; ever since, I try to avoid street action where guns might come out.) On Cedar, a one-lane street that runs two ways, I saw a police car coming in the opposite direction. I realized that this officer must have just rousted the fleeing corner hustler off his dope post. I pulled over to allow the officer to pass, waving him on because the street wasn’t wide enough for both of us. But instead, the officer pulled up close to my car and stopped, boxing me into the space I had pulled into.

The officer, a typical knuckle-cracking drug warrior with a linebacker’s build and military-style blonde crew cut, jumped out of his vehicle and immediately started blasting me with accusations. “Looking to buy some dope this morning?” he said, right up in my face. “ You got needles in the car?”

I explained that, no, I didn’t have any needles in the car because I’m not a drug user.

The officer extended his arm and pointed, pivoting each time he spoke to spotlight a different part of the neighborhood. “Heroin corner.” He turned. “Heroin corner.” He turned again. “Heroin corner.” He turned to face me. “Nothing but heroin corners around here, buddy. Now you want to tell me what you’re doing out here? Because I know you’re here buying heroin,” he said. I told him that I’m a social worker and a writer who covers drug addiction and urban poverty and I was in the neighborhood doing field work. He found the idea so preposterous that he actually laughed out loud right in my face before continuing the onslaught of accusation: “You look nervous. Why are you nervous? If you ain’t out here buying what are you so nervous for?”

I told him that he made me nervous with his aggressive way of questioning. “You are a drug addict, you are here buying drugs, and you need to give me some identification right now before I lock you up.” I gave him my driver’s license and my social work ID that shows I am employed in the criminal justice system. I told him that I work with addicts with drug charges in neighborhoods like North Camden.

“Look, brother,” the officer told me. “I don’t care where you work because I know you ain’t here working. This ID don’t mean shit—hell, I’ve locked up prosecutors in the Philly District Attorney’s Office who were over here copping bags. I’m issuing you a summons.”

I pulled up some articles I’ve written about neighborhoods like North Camden on my iPhone and asked the officer to look at them. He refused. “OK, you say you’re a writer. Maybe you are, but the fact is you’re still a drug addict. Drug addicts can be writers, too—lots of brilliant minds have also been addicts,” he said. He went on to lecture me about addiction and how I need to stop ruining my life by abusing drugs, which is ironic because I’m nearly eight years’ clean and sober. I did not mention this fact to the cop.

After further wrangling, the officer finally let me go with a warning, though he made it clear that he had added my name and address to the database of “reasonable suspects” known to the authorities and if I was stopped again in Camden I would almost certainly be taken in.

I asked a public defender in Philadelphia whether or not I could be arrested by Camden police for doing nothing but driving through a drug -infested neighborhood. She laughed. “They don’t need a reason to arrest you. They’ll just make one up after the fact. That’s what they do,” she said.

Interactions with drug-warrior cops in heroin hot spots don’t always end so favorably for innocent parties. The University of Pennsylvania’s celebrated urban anthropology professor and researcher Dr. Phillipe Bourgois has an oft-told story he shares about being stopped by police while conducting field work in North Philadelphia for a National Institute on Drug Abuse–sponsored study of shooting encampments of homeless heroin injectors and their HIV risk. When the Philly police encountered him near a hot dope corner they did more than laugh at his explanation and his credentials.

“You know, they broke one of my ribs,” he told me in his office at U Penn, “after they had already placed me in handcuffs.” He tells the story now with an ironic smirk, as if to say, “Unbelievable, isn’t it?” Professor Bourgois now carries a letter issued by the city’ police commissioner that he can give to cops while conducting field work. The most toxic aspect of drug-war policies like stop-and-frisk that attempt to keep certain neighborhoods in permanent lockdown is that it allows law enforcement to erect invisible barriers that enforce racial segregation. North Camden, like many heroin neighborhoods in cities along the Northeastern seaboard, is a predominantly Latino barrio. The fact that I was a white surely played a role in the police officer’s decision to stop me. “You don’t belong here, and you can’t come back,” he said, warning that my attempt to observe and record would not be tolerated. They want to be free to go about their business of law and order independent of scrutiny.

Despite the barrio’s deterioration, I’ve always found plenty of reasons to go there that have nothing to do with copping dope. Some of Philadelphia’s best restaurants are in the Badlands; they remain a secret because restaurant reviewers typically are scared off due to the neighborhood’s reputation. The barrio teems with eye-popping street art. North Camden, like other barrios, has a profusion of churches that burst with life, song and love on Sunday mornings. I’d encourage anyone to experience the vitality of this government-forsaken neighborhood except for the risk posed by the police to those of us who “do not belong.”

One of the messages inherent in the War on Drugs is that minority neighborhoods are dangerous conflict-torn territories that law-abiding white people has best avoid “for their protection”—or face potential arrest on suspicion of illegal activity by virtue of daring to cross the color line. Of course, the vast majority of white people who visit do so in order to score drugs; very few others may even know of the existence of these neighborhoods, although they are expanding at an unprecedented rate as towns and cities face budget shortfalls, lay off public-service employees and grow ever poorer.

When certain neighborhoods are converted to occupied territories under virtual marshal law sealed off from the rest of the urban population by the law-enforcement lie that only bad people (addicts) go to bad places (barrios) to do bad things (get high) becomes an unwritten policy that perpetuates exactly the social problems it professes to solve. This serves to keep the poor and the privileged living in parallel universes. As a society, we need to move in precisely the opposite direction; our public institutions and spaces need to become more open and integrated in order to save the health of our cities.

The experience of journalists covering the Occupy Wall Street crackdown revealed that when police cut off the press from witnessing police interactions with a certain community, it’s probably because the cops are doing something that they want to keep hidden from the public. We are frequently being reminded that a free press is essential to democracy; when the press is locked out or handcuffed and arrested, it is the people’s responsibility to risk bearing witness.

Jeff Deeney, a Philadelphia social worker and writer in recovery, pens a weekly column for the The Fix. He is also a contributing writer for Newsweek/Daily Beast.